Don’t panic: interpretation of error messages

Error messages are your friends. Although your immediate reaction to an error message may be one of anxiety, most of the time the message (e.g., text in a dialog box, or the location of a red squiggly line in <oXygen/>) contains information you’ll need in order to correct a problem. Integrated development environments, web browsers, and command lines can all offer you important advice about how to correct problems in your code, but only if you pay attentiont to that advice! Below we explain how to read and understand a few common types of error reporting in XML technologies and Python. Your goal in reading this explanation is not primarily to learn about those specific errors; it’s to learn, in a general way, how to engage confidently and effectively with error reporting during development.

Don’t ignore or suppress error messages

New coders sometimes try to reduce the reporting of errors under the mistaken impression that they are reducing errors. That strategy is a mistake. The most damaging error is the one that you don’t know about, the one that gives you an incorrect response without your knowledge.

Read the error message

Some types of error messages are difficult for new coders to understand, but they become less opaque with practice, and you need to learn how to read them in order to diagnose and fix your own errors. And in situations where you can’t understand an error message, you need to report the text of the message when you ask for help. Nobody is likely to be able to help you if all you say is “I tried X and it didn’t work” or “I tried X and I got an error”. When you ask for help, report the specific error message, and the starting point for reporting an error message is reading the message yourself.

Don’t suppress the error message

Most programming languages and development environments provide some degree of control over the reporting of errors, and new developers sometimes confuse minimizing error reports with reducing errors. For example, in XSLT and XQuery you have a choice about whether to specify the datatype of a variable when you declare it (using as in XQuery or an @as attribute in XSLT). If you don’t specify the type, you’ll see fewer error messages, but that doesn’t mean that you’ll make fewer errors. It just means that when you make a mistake and use data of the wrong type, what your code does will differ from what you think it does, and you’ll have put yourself at risk of getting bad results because you won’t know about the difference. At least during development, you’ll make fewer errors if you take advantage of any error checking and reporting the language or environment makes available.

Errors with XML technologies

If you’re using the <oXygen/> XML Editor, which validates strictly, you’re going to be notified of most errors. Sometimes, though, error messages show up in odd places, which can confuse editors of every experience level. In XML, there are two ways to evaluate a document for errors: by well-formedness and by validity.

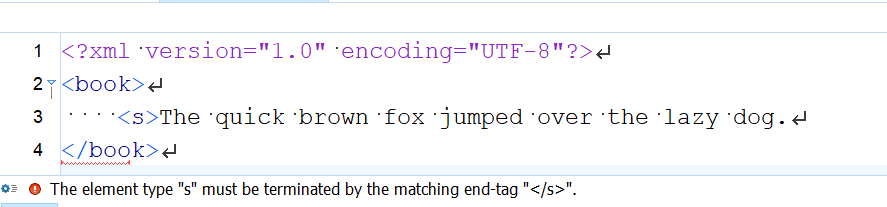

Well-formed documents follow rules that apply to every XML document, meaning there is one root element, there are no overlapping hierarchies, every start tag has a corresponding end tag, etc. In the case illustrated here, for example, <oXygen/> is displaying a red squiggly line because the

Well-formed documents follow rules that apply to every XML document, meaning there is one root element, there are no overlapping hierarchies, every start tag has a corresponding end tag, etc. In the case illustrated here, for example, <oXygen/> is displaying a red squiggly line because the <s> element is missing its end tag, which is a well-formedness violation. The location of the red squiggly line might seem to suggest that there’s an error with the </book> end tag, but what it’s really telling you is that the error is just before that end tag. It might seem most natural to a human to write the </s> end tag at the end of line 3, but writing it at the beginning of line 4, before the </book> end tag, would also be well formed. <oXygen/> can’t know that you’ve forgotten the </s> end tag until it sees the </book> end tag, which is why it can’t report the error on the preceding line, where a human might think it occurred. The message that <oXygen/> displays at the bottom of the editing window, though, makes it clear that the correction should be to add the missing </s> end tag.

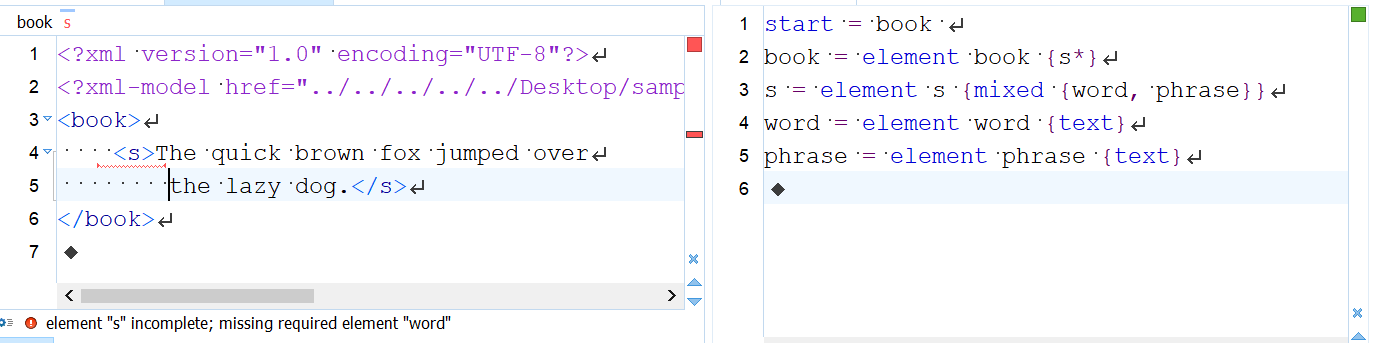

Validity is defined as conformity to the schema(s) associated with the document. (Among other things, this means that if there is no schema, all errors are necessarily well-formedness errors.) The following image illustrates a validation error in the XML document instance to the left. The error is that the <s> element on lines 4–5 does not contain a <word> element, although the Relax NG schema to the right, which is being used for validation, requires that an <s> element contain exactly one <word> and one <phrase> element, intermixed optionally with plain text. The squiggly red line identifies the <s> element as the location of the error, and the error message displayed below explains that a required <word> element is missing.

This error message tells us one of two things: either we should change our markup to fit the model in the schema, or change the model to fit the markup.

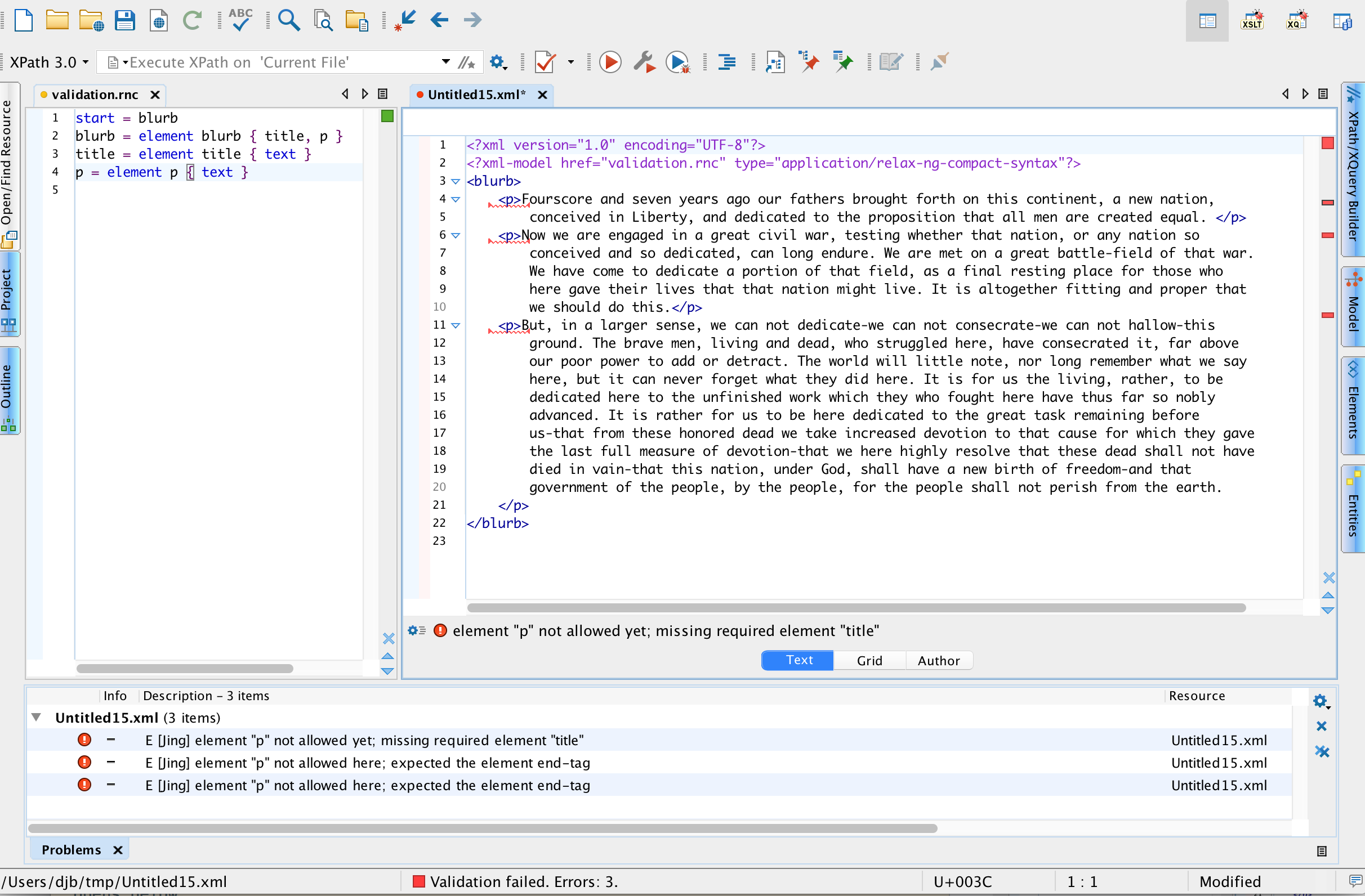

The real-time validation error report at the bottom of the <oXygen/> editing window shows only one error at a time, but if there are errors in multiple locations, you will see squiggly lines and red bars in the right margin for all of them. Consider the example below:

The schema, to the left, requires a <blurb> to contain exactly one title followed by exactly one paragraph, but the document instance, to the right, has three paragraphs and no title. There are three validation errors: the missing title and the two extra paragraphs, and there are three squiggly red lines and three small red bars to the right (plus the red square above them, which is a summary report that there’s somthing amiss). The textual error message at the bottom reports only one error (the last), but if you click the red check icon above the editor screen, you’ll open a window that lists all error messages below:

Errors in Relax NG

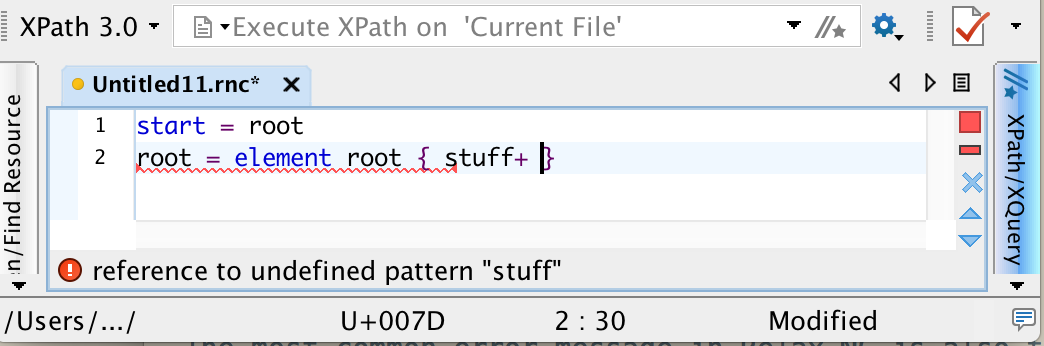

Reference to an undefined pattern

The most common error in Relax NG is also the easiest to fix: a reference to an undefined named pattern. The pattern name you have not defined appears in the error message itself, and a red squiggle appears under the line where you refer to the undefined pattern. Most often, this error message appears because you’ve referred a pattern you haven’t defined yet, and you can fix it by adding the definition. In other cases, though, you may have mistyped the name of the pattern.

The most common error in Relax NG is also the easiest to fix: a reference to an undefined named pattern. The pattern name you have not defined appears in the error message itself, and a red squiggle appears under the line where you refer to the undefined pattern. Most often, this error message appears because you’ve referred a pattern you haven’t defined yet, and you can fix it by adding the definition. In other cases, though, you may have mistyped the name of the pattern.

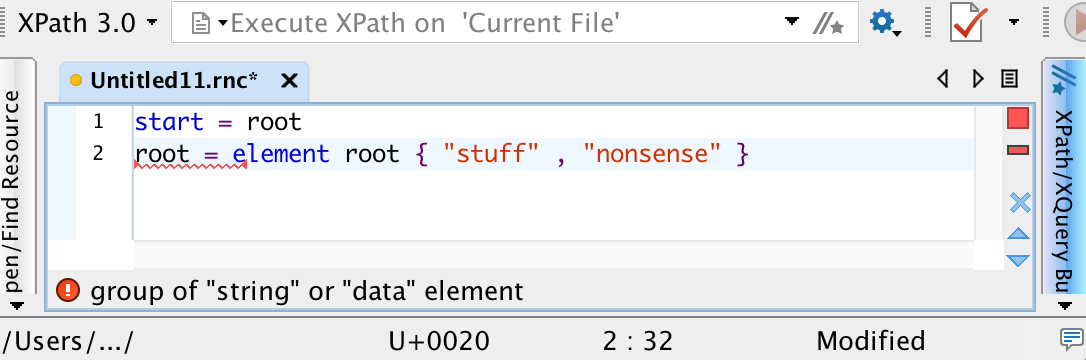

Group of “string” or “data” element

This error appears when you define an element or attribute with a group of strings, rather than just a single string or datatype, since Relax NG doesn’t permit patterns that juxtapose two string values. In most cases, you typed a comma (representing sequence) when you meant to type a pipe (representing choice).

This error appears when you define an element or attribute with a group of strings, rather than just a single string or datatype, since Relax NG doesn’t permit patterns that juxtapose two string values. In most cases, you typed a comma (representing sequence) when you meant to type a pipe (representing choice).

No error message, but something isn’t right

When you develop a schema after the fact, to formalize the structure of an XML document, the schema itself may be valid, but an error message may appear when you validate the XML against the schema. In this development scenario, though, we’ve stipulated that the XML says what it says, so if it isn’t valid against the schema that we’re crafting to model it, we need to fix the schema.

In the example above, the error message tells us we must have a word element before a phrase element, as we’ve used a comma in the schema to indicate we require exactly one of each one, in that order. Note that <oXygen/> puts squiggly red lines in two places, once for <word> and once for <phrase>, even though you moving just the <word> or just the <phrase> (that is, one edit operation) will fix both problems at once. In other words, to a human this might be one error, but to <oXygen/> it looks like two.

To diagnose and fix this type of error, look specifically for phrases like “not allowed yet” and “not allowed here”. Does your schema require sequence where you mean choice? Or vice versa? Did you forget to mark something that repeats as repeatable? Error messages like these don’t point to the Relax NG because the Relax NG itself is valid, but we’ve stipulated for this example that the XML cannot be edited, and that means that the schema needs to be revised to match the reality of the document instance. In other words, it looks like the problem is invalid XML, but it’s really a schema error, according to which the schema doesn’t model what you want it to model.

Errors in XPath and XSLT

Each XSLT error message comes with its own unique identifier (e.g., integer division by zero is error FOAR0001), which you can search online to find more information about the problem. This is especially useful when you start looking at StackOverflow, as more than likely someone else has been having your problem too, and someone else can’t wait to explain it to you. For example, suppose you’ve introduced an <xsl:sort> element to sort your output, and you get the following error message:

XTSE0010: An xsl:value-of element must not contain an xsl:sort element

You may not always be able to predict where to find a more detailed explanation, that is, in this case, whether to look under <xsl:value-of> or <xsl:sort>, and the explanatory text may not always be precise. In this case, Michael Kay tells us that:

<xsl:sort>is always a child of<xsl:apply-templates>,<xsl:for-each>,<xsl:for-each-group>, or<xsl:perform-sort>

This tells indirectly that <xsl:sort> cannot be a child of <xsl:value-of>. The error message is imprecise, though, because an <xsl:value-of> element can actually contain an <xsl:sort> element; the constraint is only that it cannot contain it as a child element. For example, the following XSLT is valid, even though in it <xsl:value-of> contains <xsl:sort>:

<xsl:value-of>

<xsl:for-each select="//title">

<xsl:sort/>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:value-of>

Reading stack traces in Python

What are stack traces?

A stack trace, also called a traceback, is a type of error report produced by Python and other programming languages that shows the chain of events between the line of code that causes an error to arise and the part of the program where the error actually occurs. For example, if function A calls on function B and the user passes input into function A that function B cannot handle, a stack trace will report an error chain from function A (the most recent call, which led to the error) back to function B (the place where Python could not do what it was asked to do). Stack traces can be as deep as they need to be, and being able to read a stack trace is necessary for finding and fixing coding errors.

Getting an error report with an interactive command

We’re going to make some deliberate errors in order to produce a stack trace for illustrative purposes, and the first type of error we’ll provoke will be a “divide-by-zero” error. (Programming languages treat division by zero as undefined, and raise an error when you try to perform it.) To produce a divide-by-zero error at the command line, open a command-line session, type python to launch an interactive Python shell, and the type 6 / 0 at the Python command line. You should get an error report similar to the one below:

Python 3.6.1 (v3.6.1:69c0db5, Mar 21 2017, 17:54:52) [MSC v.1900 32 bit (Intel)]

on win32

Type "help", >>> 6/0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

The first two lines are feedback created when we open the Python shell (yours may look slightly different), and on the third line we’ve typed 6 / 0 at the Python shell prompt (>>>). The last three lines are the error report. (To exit a Python interactive shell when you’re finished with it, type either quit() or Ctrl-d at the Python prompt.)

This error report doesn’t show much information because there isn’t much to trace (we had just one brief line of code) and Python interactive shell doesn’t have a filename, so it reports only <stdin> (that is, input that you typed directly) as the location of the error.

To produce, for pedagogical purposes, a more interesting stack trace, let’s define and call some functions.

Getting an error report with a user-defined function

Copy and paste the code below into a new .py document (you can create one in any plain text editor):

def my_function():

zero = 0

anumber = divide(zero)

return anumber

def divide(denominator):

numerator = 6

return numerator / denominator

my_function()

Save the file; you can call it someting like my_filename.py. The last line runs my_function(). my_function(), in turn, defines a variable called zero with the numeric value of zero, and then passes that value into a call to the divide() function. Whatever the divide() function returns gets assigned to the variable anumber, which my_function() then returns. Meanwhile, the divide() function, in turn, receives the value passed into it, assigns it to the variable denominator, and divides the denominator into a numerator value of six. In this case, since the value passed into the divide() function is equal to zero, we are trying to divide 6 by 0, which raises an error because, as noted above, division by zero is treated as undefined.

To run this program, open a shell prompt, navigate to the directory holding the file, and type python my_filename.py. You should see something like the following error report:

cl2-wifi-10-215-50-16:tmp djb$ python div_by_zero.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "div_by_zero.py", line 10, in <module>

my_function()

File "div_by_zero.py", line 3, in my_function

anumber = divide(zero)

File "div_by_zero.py", line 8, in divide

return numerator / denominator

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

The first line is our command prompt (through the dollar sign), followed by python my_filename.py, which we typed. The rest is the error report, and it’s most helpful to read a traceback, or stack trace, from the bottom up. It shows that there’s an error in line 8 of the file, in the divide() function, and that’s the line that performs the illegal division by 0. The stack trace tells you (on the second line of the sample, above) that the most recent call is last, which is to say that line 8 (which contains the actual division operation) got called by the stack item above it, line 3 of the same file , inside the my_function() function. That’s the line that called the divide() function in the first place, and therefore caused it to perform the illegal division. The error inside my_function(), in turn, is the result of the stack item above it, where <module> (the main routine in the div_by_zero.py file) called my_function() on line 10.

Type error

Many Python functions and operations accept only specific types of arguments. For example, the abs() function, which returns the absolute value of a number, accepts only numeric values. Thus, abs(-2) returns 2 but abs('minus two') returns a type error.

Try saving the following code to a file called absolute.py and then running it with python absolute.py:

def absolute(input):

return [abs(i) for i in input]

absolute([1,-2,3,'obdurodon'])

You should see something like the following stack trace:

cl2-wifi-10-215-50-16:tmp djb$ python absolute.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "absolute.py", line 3, in <module>

absolute([1,-2,3,'obdurodon'])

File "absolute.py", line 2, in absolute

return [abs(i) for i in input]

File "absolute.py", line 2, in <listcomp>

return [abs(i) for i in input]

TypeError: bad operand type for abs(): 'str'TypeError: bad operand type for abs(): 'str'

The first line is our command prompt (through the dollar sign), after which we’ve typed the command. The rest is the stack trace. Reading from the bottom up, the error is a TypeError, where we tried to apply the abs() function to a string (‘str’) value, which is prohibited. That error occurred inside a list comprehension (<listcomp>) in line 2 of our file. The list comprehension was part of a function called absolute(), and the error was in line 2 within the function. The absolute() function, in turn, was called from the main module of the file (<module>), on line 3 of our file.

If we look at the same stack trace from the top down, the line of code where we invoke the absolute() function doesn’t know what kinds of arguments absolute() can process without error. absolute(), in turn, calls on the Python library function abs(), but absolute() doesn’t know what types of values abs() can accept without error. For that reason, the error is only flagged when it reaches the abs() function.

Stack traces and modules

Suppose we save our absolute() function in a separate module (file) and import it into another Python script. First create the following file and save it as absolute.py:

def absolute(input):

return [abs(i) for i in input]

Now create the following file and save it as test.py:

from absolute import absolute

values = [1, -2, 3, 'obdurodon']

absolute(values)

test.py imports the absolute() function from absolute.py, creates a variable called values equal to a list of four values, and then applies the absolute() function to that list. It produces the following stack trace:

cl2-wifi-10-215-50-16:tmp djb$ python test.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 3, in <module>

absolute(values)

File "/Users/djb/tmp/absolute.py", line 2, in absolute

return [abs(i) for i in input]

File "/Users/djb/tmp/absolute.py", line 2, in <listcomp>

return [abs(i) for i in input]

TypeError: bad operand type for abs(): 'str'

Once again, the first line is our command prompt (through the dollar sign), followed by the command, which we typed. The errors appear in the same logical places as when all of the code was in one file. Reading from the bottom up, the abs() library function raises a type error when applied to a string, the string gets passed to abs() inside a list comprehension, the list comprehension occurs inside our absolute() function, and the absolute() function gets called on line 3 of our test.py file. Here, though we also get the name of the file that contains the absolute() function. The fact that a stack trace reports the filename, the line number, and the text of the offending line is a small convenience with code as simple as this example, but in a more complicated project, where modules (files) may call modules that may themselves call modules, the stack trace, as the name implies, allows us to trace the sequence of calls from the line in our code that provoked the error all the way back to the location where Python detected and reported it.

How to read a stack trace

There are three important moments in a stack trace: the top (the line of our code that provoked an error), the bottom (the place where the error was recognized and reported), and the moment where the errors make the transition from the code we wrote (we wrote the call to the absolute() function, and the call to abs() within the absolute() function) to code that is not under our control (the abs() function itself, which is part of the core Python library).

In this case, that combination of information tells us that the error is happening because we are passing an illegal value from our invocation of the absolute() function into the body of that function, and then to the abs() function in the core Python library. It also tells us that if we want to trap and handle the error ourselves (for example, we could report illegal values to the user in a more graceful way than by dumping a stack trace, or we could silently ignore illegal values), we need to do it in code that we control.